Most students walk into their first organic chemistry lab and see just glass everywhere.

Look closer, though, and there are actually two worlds of glass sharing the same bench space, each with a completely different purpose and personality.

TL;DR

- Beakers & cylinders → molded glass, cheap, great for everyday mixing at atmospheric pressure.

- Condensers, jointed flasks, adapters → hand-blown borosilicate, engineered for heat, cold, vacuum, and complex setups.

- Using molded glass under heat or vacuum is unsafe. Organic labs rely on hand-blown glass because it’s built for those stresses.

From “Just Glass” to Two Different Worlds

I’ll never forget the first time I walked into an organic chemistry lab. Most students just see “glass everywhere.” But after years of working with it, I see something very different: two distinct worlds sharing the same bench space.

On one side, you have the familiar faces from general chemistry—beakers and graduated cylinders. They’re the reliable, everyday soldiers.

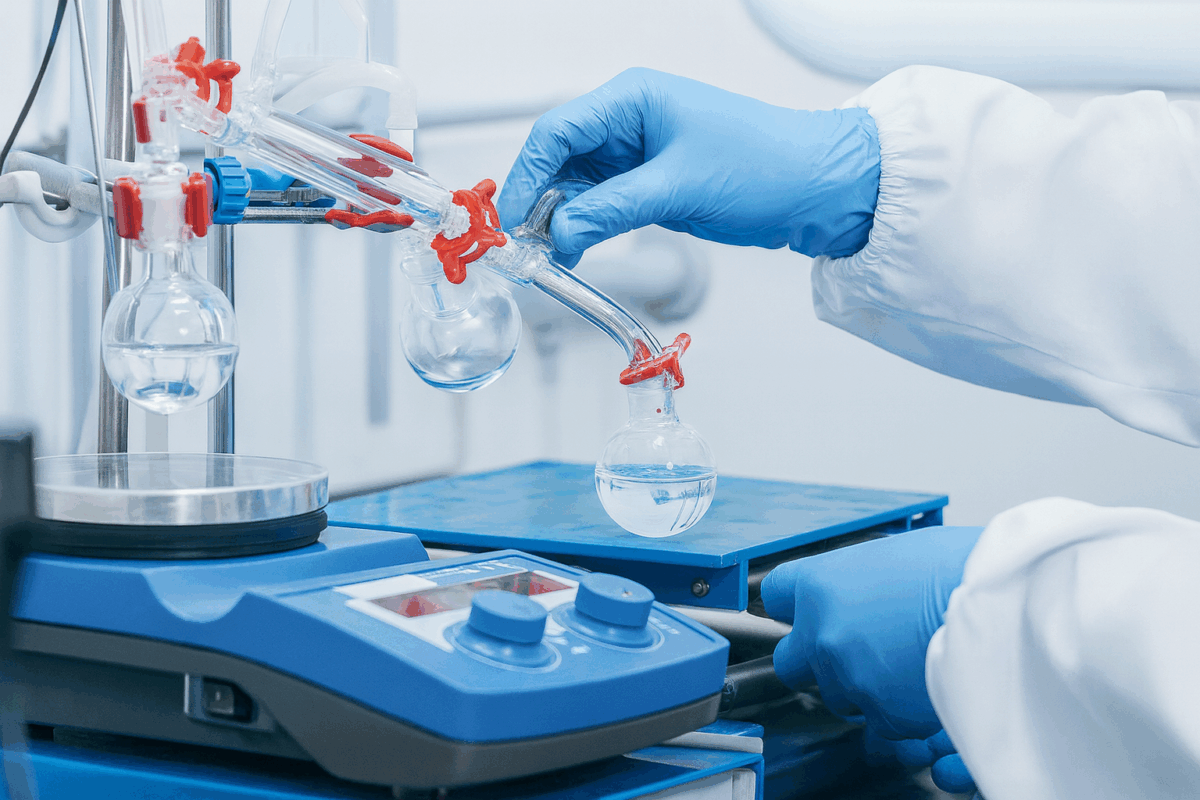

On the other side lies the real magic: long condensers, three-neck round-bottom flasks, distillation heads, vacuum adapters—pieces with standardized joints that click together like scientific Lego.

Here’s the secret most students don’t learn until later:

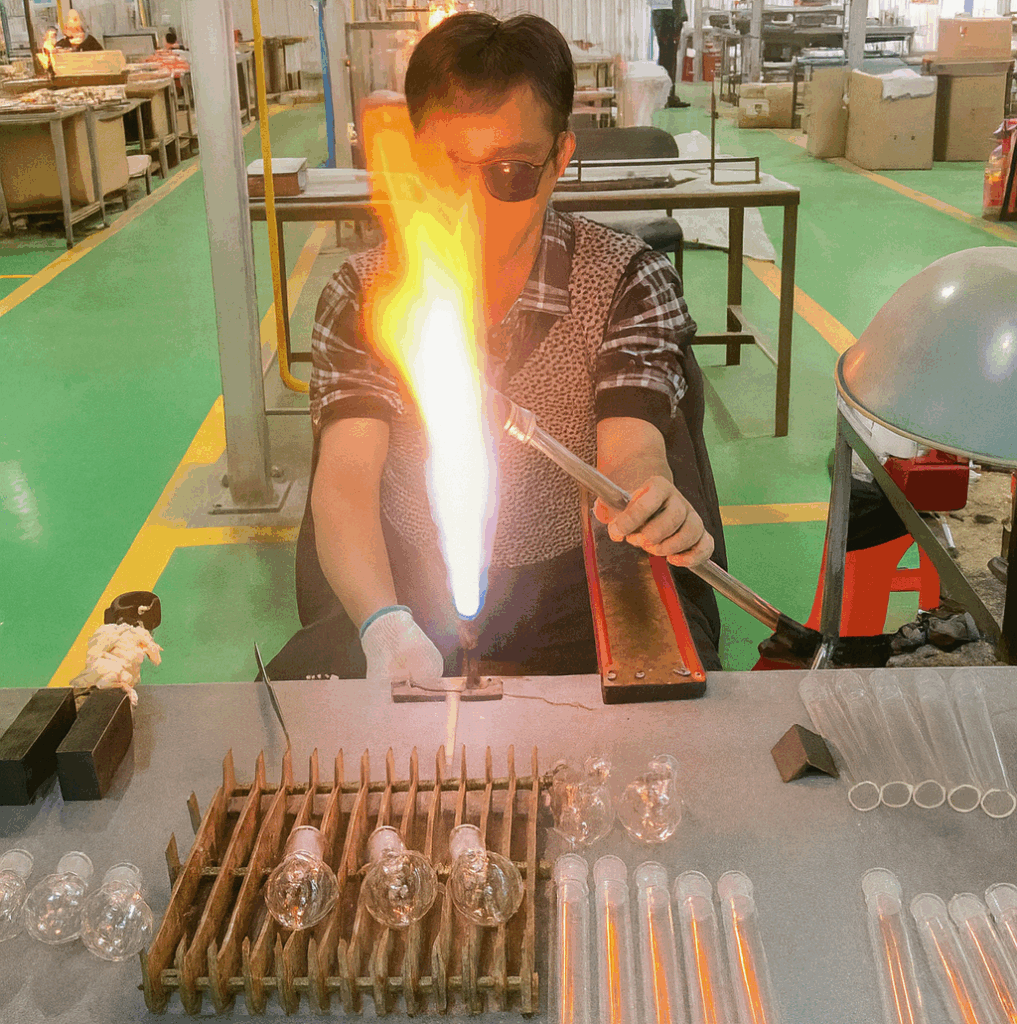

Those complex pieces aren’t stamped out of molds. They’re hand-blown—born from flame, skill, and careful annealing.

If you remember only three points from this article:

- Molded glass is perfect for gentle, everyday work.

- Hand-blown borosilicate is designed for heat, cold, vacuum, and modular systems.

- Using the wrong glass under stress can cause sudden breakage, solvent sprays, or dangerous implosions.

The Two Personalities of Lab Glass

Think of lab glassware not as different “types,” but as different crafts.

Molded Glass: The Mass-Produced Workhorse

Molded glass is made by pouring molten glass into a metal mold—like baking a cake in a pan.

Common pieces

- Beakers

- Graduated cylinders

- Erlenmeyer flasks

- Petri dishes

- Simple storage bottles

Strengths

- Very inexpensive

- Durable for everyday mixing, measuring, and storage

- Easy for teaching labs to stock in large numbers

Weaknesses

- Walls may be slightly uneven

- Strength depends on perfect annealing—shortcuts leave hidden stress

- Cannot form precise standard taper joints

- Poor performance under vacuum or extreme temperature change

Most importantly, mold cooling creates internal stresses you can’t see—but the glass will certainly “feel” them under heat or vacuum.

Molded glass is perfect for a calm day at atmospheric pressure. Push it beyond that, and it may just let you down.

Hand-Blown Glass: The Artisanal Athlete

This is where the craft begins.

A glassblower starts with a simple borosilicate tube, heating it in a flame to stretch, bend, flare, and shape it. They fuse pieces together and finish with standardized joints (14/20, 19/22, 24/40).

Why it matters

- Complex shapes are easy. Allihn condensers, multi-neck flasks, cold traps, custom adapters—shapes impossible to mass-produce in molds.

- Engineered strength. The blower controls wall thickness and reinforces stress points.

- Proper annealing. The piece is heated and cooled in a kiln to remove internal stress—critical for vacuum safety.

- Part of a modular system. Every joint is designed to be compatible with global standards.

Yes, hand-blown glass costs more. But you’re paying for precision, safety, and reliability under extreme conditions.

What Organic Labs Actually Do to Glass

Students see “a container.” Experienced chemists see a component in a high-stress system.

1. Thermal Shock

Going from an ice bath to a 200 °C oil bath can shatter poorly annealed or uneven glass. Hand-blown borosilicate expands evenly and can survive these transitions far better.

2. The Crush of Vacuum

Vacuum doesn’t “pull” glass apart—it crushes it inward. Any weak spot—a bubble, thin area, or sharp transition—can fail suddenly.

My golden rule: If I don’t know its history, it never touches my vacuum line. Unknown glass is a silent liability.

3. The Lego Principle

Organic chemistry rarely uses a single piece of glass. You build reflux systems, distillation trains, Schlenk-line assemblies, vacuum filtrations, and multi-step setups.

This only works when every jointed piece from different brands fits and seals consistently. That’s the promise of hand-blown systems.

A Quick Safety Checklist

Before starting your experiment, ask:

- Heat or extreme cold? → Use hand-blown borosilicate.

- Vacuum or pressure? → Hand-blown only. Never risk “mystery glass.”

- Visible damage? Star cracks, chips, large bubbles, deep scratches? → Retire immediately.

- Room-temperature mixing/storage? → Molded beakers or bottles are perfect.

When in doubt, ask yourself: Would I stand in front of it during vacuum or heating? If not, it doesn’t belong in your hood.

Choosing Your Glass Allies: A Practical Brand Guide

Once you move beyond simple beakers and start building complex setups, the brand of glassware you choose becomes a critical decision. It’s not just about budget; it’s about trust. From the assemblies I’ve used and seen in labs around the world, the landscape of hand-blown glass breaks down into three clear tiers.

The Gold Standard: When Failure Is Not an Option

Brands like Chemglass and Wilmad-LabGlass set the benchmark.

Why people choose them

- Extremely tight dimensional consistency

- Excellent joints and finishing

- Strong support for custom apparatus

If your lab runs demanding, high-vacuum or high-temperature experiments every day, this level of craftsmanship earns its price.

The Smart Value Tier: Reliable Performance Without the Premium

Not every teaching lab or startup research group has a research-institute budget. This is where Laboy Glass and similar value-oriented makers fill an important niche.

What they get right

- True hand-blown borosilicate 3.3

- Proper standard taper joints

- Consistent performance for most academic and routine synthetic work

- Allows departments to equip every bench affordably

This tier offers dependable, safe, and compatible glassware without premium pricing—and that’s why you’ll now find it widely used across universities and teaching labs.

Marketplace Bargains: When Low Price Carries Hidden Risk

The internet is full of ultra-cheap glassware from marketplace-driven brands. Some pieces are usable, but quality and annealing consistency can vary significantly.

For procurement: treat unusually low prices with healthy caution. In organic chemistry, glassware is safety equipment. If you don’t know the annealing history or joint precision, you don’t know whether the glass will behave safely under stress.

The Bottom Line

Organic chemistry doesn’t use hand-blown glass because it looks elegant. It uses it because it’s engineered for the realities of synthetic work—heat, cold, vacuum, modularity, and safety.

Glassware isn’t just something that holds chemicals. It’s a partner you rely on when the experiment gets real.